At a time when the fundamental right to vote has increasingly become a partisan pawn, deep-seeded misconceptions surround who can and cannot vote, specifically as these rights apply to people who have been previously incarcerated.

“I would have voted, but I didn’t know I could.” At the American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana, we get calls like this after every election. It is devastating. My hope is that every Hoosier owns their power and exercises their right to vote. But you can’t use your rights, unless you know your rights.

Voting restrictions for people who have been previously incarcerated vary from state to state, leading to confusion, mass-misinformation and misapprehension. The problem is broad. Even those working in re-entry organizations or in elected offices confess they don’t know the voting laws well enough to share accurate information. Election laws are governed by the individual states, and some are deeply rooted in Jim-Crow era policies. For example, in Vermont and Maine, individuals who are incarcerated never lose their right to vote, while in other states, millions have permanently lost their right to vote.

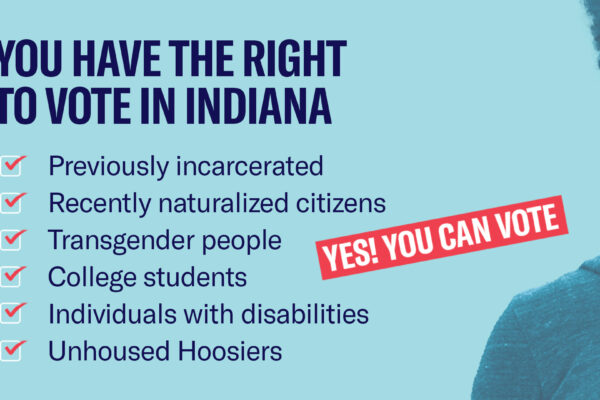

So, let’s clear this up: Indiana is one of 24 states (including D.C.) where people who have been previously incarcerated can vote upon release. Individuals lose their voting rights only while incarcerated, and receive automatic restoration upon release. Individuals on parole, probation, home detention, or people who are in jail awaiting trial, can vote. Yes. You can vote.

The restoration of the right to vote upon release back into the community, gives individuals an opportunity for reengagement and a chance to be full members of our democracy. It is the type of engagement we should be encouraging as a society.

Unfortunately, scare tactics in a few states and clouds of uncertainty in every state, keep previously incarcerated individuals away from the polls. In states such as North Carolina and Texas, where individuals’ voting rights are restored only after they have completed their parole or probation programs, we have recently seen a weaponization of the ballot box by a handful of prosecutors. Individuals have been prosecuted for voting fraud, even though these individuals honestly believed they had the right to vote upon release from prison. When people who have been previously incarcerated hear these stories, it leads to confusion about their rights, and fear of prosecution and further jail time. Voting just doesn’t seem worth the risk.

Indiana had the lowest midterm voter turnout in 2014 with just over 28%. While Indiana’s voter turnout ranking rose in the 2018 and 2020 elections, our state was still ranked in the bottom eleven states both years. We can do better. These rates suggest that Indiana does not have a voter fraud problem, we have a voter turnout problem. As a part of our obligation to engage all citizens in our democratic institutions, Hoosiers share the responsibility to inform individuals who have been released from jail or prison -- over 25,000 in 2016 and 2017 alone -- of their right to vote.

Barriers to the ballot exist beyond Indiana. In addition to states that restrict access to the ballot for people who are formerly incarcerated, since 2008, states across the country have passed measures to make it harder for Americans—particularly black people, the elderly, students, and people with disabilities—to exercise their fundamental right to cast a ballot. These measures include cuts to early voting, voter ID laws, and purges of voter rolls.

As the 2022 midterm elections approach, the ACLU of Indiana is working tirelessly to share this message with Hoosiers: Yes! You can vote. If you have been previously incarcerated, have a disability, are a college student, are transgender or have been recently naturalized – you can vote!